North to Orkney in 2008

photographed by Adrian and Gill Smith

Assorted Photos – click on the thumbnail for the full-size image

Birds and flowers are summarised separately for the convenience of wildlife buffs!

Working our way North

Starting on the mainland near St Andrews, then the ferry boat across to the Orkneys. This set of pictures is mostly for the geologists – Gill & Richard spent a happy day fossicking around the foreshore near Crail (on the Fife Coastal Trail) and turned up a nice example of slickensides as well as some splendid coal-measures fossils. The roots are Stigmaria and belong to the classic coal-forming Lepidodendron from around 250 million years ago. This was a kind of giant club-moss – the diamond pattern you can see on the last picture is a print of the leaf scars.

| Crail foreshore. Looking south across the Forth. |

|

| Slickensides. This is where a big earthquake happened a long time ago, leaving a smooth, hardened and polished face as the rock slipped. |

|

| Slickensides showing scratches. You can work out the direction of movement from the grooves in the slip plane. |

|

| Slab with embedded roots. All the good fossils were in the bottom of this layer – luckily a piece had broken off and was lying upside-down just below. |

|

| Stigmaria with hammer for scale. This is the most commonly-found cast of the Lepidrodendron root, and often lies under coal seams. |

|

| Stigmaria showing bark as coal layer. A much more exciting find, as the coal layer is very soft and would only survive a few more tides. |

|

| Stigmaria rootlet. The root tip again has the coal layer at the end. |

|

| Lepidodendron bark print. On a different slab a little further along. |

|

Too far to make the ferry in one day, so a gentle run up the coast via Black Isle to overnight at the Granite Villa guest house in Golspie. This far north-east coast is much under-rated as a holiday destination – Dornoch has one of the great golf-courses in the UK (no, the world) and the local climate benefits from all the high stuff to the west. Good to have the chance to enjoy it.

| Lighthouse at Tarbat Ness. The banks of gorse were the most remarkable feature of this piece of coast. |

|

| Whinny bushes in flower. No, this isn’t some exotic tropical plant, just good old gorse going a bit crazy! |

|

| Broch at Carn Liath. If you ever stop here, do ignore the signs that send you half a mile up the road to a ‘safe’ crossing and just hop the barrier in the obvious place! One of the best brochs on the east coast, being quite simple and still mostly intact as built. |

|

Across the Pentland Firth to Orkney

The views from the boat were much better on the way back, so we skip straight on to a bit of stone-circling (still in slightly dodgy weather) as we made our way down to the Inn at St Marys for a 3-night stay. This gets a very strong recommendation – Mike and Shona definitely get the ‘best breakfast’ award for the trip and the showers actually made you want to get up in the mornings! What’s more they did wide-screen Sky so we could watch the US Open at bedtime, while using their WiFi link to throw away 6 days of junk mail.

| Stone of Stenness with pixie. The stone really is this tall – note the diagonal top which seems to be the natural cleavage of the local sandstone blocks, but was used to great artistic effect by the builders. |

|

| Stenness with Hoy in the background. There is a feeling that the near pair of stones is a winter sunrise sighter on the left-hand peak on Hoy. |

|

| Ring of Brodgar. This one is almost complete and seems to be a perfect circle. The stones are bigger than they look, as can be seen from the next picture. |

|

| Brodgar with sheltering human for scale. Tim probably won’t be using this for his facebook image! |

|

The Broch at Gurness was another highlight of the trip – we had taken the evening tour at Maes How and needed to kill a couple of hours, and arriving here after it had ‘closed’ was a very good move. As you can see from the second view, we were not alone in this! The broch itself was very well-preserved, but the iron-age village surrounding it was nearly as clear as the more famous Neolithic example at Skara Brae, and you could still mosey around inside the huts.

| Gurness perimeter ditch. The broch itself is entered through the dark oblong in the middle distance. |

|

| Iron-age huts surrounding Gurness. As you can see, the local sandstone is good for furniture as well as standing stones. |

|

| Main entrance to Gurness broch. This must have been a very handsome front door in its heyday. |

|

| Detail of front door at Gurness broch. Probably the nearest thing to the Lion Gate at Mycenea that you will get in the UK. |

|

| Gurness interior. Again there is a lot of very well-kept stone furniture. |

|

| Coastline at Deerness. Arctic Skuas were the highlight of this walk, but no pictures of them, unfortunately. |

|

| The Gloup. This was a prime example of a ‘Geo’ which were very common in the sandstone cliffs where a line of weakness had been taken well inland. This one still has about 50 yards of cave on the seaward side before it opened out into a deep cleft. |

|

Chambered Cairns at Wideford and Cuween Hills

As always, the best sites are the ones you can’t get a bus to. Wideford Hill and Cuween Hill are both a little off the beaten track, and both are best visited with crawling gear and a good torch. Both are well worth the effort, being essentially complete and in superb locations. The male Hen Harrier posing on a fencepost beside the track was an unexpected bonus.

| Wideford Hill chambered cairn. The original entrance tunnel is still there, but access is now via the modern hatch. |

|

| Wideford entrance hatch. Note the box (top right of picture) which has a torch in it for you to use. |

|

| Wideford interior. This shows the corbelled structure of the side-chamber roof very nicely. |

|

| Cuween Hill location. Only a short walk from the car, but this still seems to put off the majority of visitors. Pity, ’cos this was the best of the lot! |

|

| Cuween Hill entrance. Yes, you have to open the sheep-gate and crawl in. |

|

| Cuween interior. We might run a caption contest on this one. |

|

| Cuween side chambers. Here you get a good look at the simple slab roof in the main chamber. |

|

| Cuween roof structure. The side chambers were corbelled, with rather smaller closing slabs. |

|

Skara Brae and the cliffs at Yesnaby

Onward to Skara Brae and the cliffs at Yesnaby to look for Primula scotica which had taken advantage of the glorious weather the month before and flowered early. Damn!

| Windy day. Tim may want this one! |

|

| Skara Brae overview. We were a little worried that this may have been ‘heritaged’ to death, but it was still worth the trip. I can see why they don’t let you climb all over it these days – visitor numbers are just too high. |

|

| Skara Brae house. You can walk around the edge and look down into them, and there is a very good facsimile of hut-7 by the visitor centre to give a feel for what it was really like. |

|

| Skara Brae interior. More good use of local stone to create a Neolithic sideboard. |

|

Mostly for the geology again (if you ever see a better example of cross-bedding, I’ll be very surprised) and the usual impressive coastline.

| Yesnaby cliffs. Sandstone does a great job on holding the vertical when the sea takes out the bottom. |

|

| Man in Black. Another one for Tim’s facebook set! |

|

| Cross bedding in the stack. Look carefully at the angles in the stone on the exposed face. |

|

| Cross bedding detail. Nice patch of Thrift just to set it off. |

|

| Yesnaby Castle. Nothing like a bit of backlit water to get the shutter clicking! |

|

The Italian Chapel, the Brough of Birsay and back to Stromness for the Hoy ferry

Next stop, the Italian chapel, just across the first of the Churchill Barriers from the guesthouse (on the extreme left of the panorama). The barriers were built from concrete blocks, cast and placed by Italian POWs (in pretty obvious contravention of the Geneva Convention BTW) who used their skills and spare time to turn an unpromising Nissen hut into a quite marvellous church, now lovingly preserved by the islanders.

| Italian chapel showing original exterior. This has to be the least photogenic east end of any church in Britain. The miracle is what they have done to the interior … |

|

| Italian chapel looking west. Now you begin to get a clue that there is something special here, but there is lots still to come. |

|

| Italian chapel showing west front. Now this is getting a bit special – apparently the bell was faked with papier mache until the locals gave them a salvaged ship’s bell to replace it! |

|

| Italian chapel - a first look at the interior. If this doesn’t give you a Wow! moment, then I don’t know what would. Everything is just painted, even the brickwork in the vault. |

|

| Italian chapel east end. All made out of simple local materials – mostly cast concrete liberated from the barriers they were building. |

|

| Italian chapel - detail of altarpiece. If you don’t click on anything else, click on this one! It deserves to be seen at full size. |

|

| Italian chapel - fake arcading. This is very hard to see as it really is – just a plaster surface with careful use of light and shade to get that authentic 3D look. |

|

The Brough of Birsay is somewhere you can only visit at low tide, which keeps it a little off the beaten track. The settlement is almost entirely Viking, and still had the feel of a living village. Somewhere to spend most of a lazy summer afternoon doing very little.

| Birsay location. You can sit in the doorway of a Viking longhouse and enjoy the same view as they had, at least while the sun shines. |

|

| Birsay church. There was a small monastic community here in the 11th century, and much of the church remains above ground. |

|

| Birsay oystercatchers. Posing, as oystercatchers do (when not panicking about something). |

|

| Birsay sauna. Yes, Vikings haven’t changed – never mind the rape and pillage, get the sauna organised. |

|

| Birsay - young wheatear. Family was using the earth banks around the houses to meet up at feeding time. |

|

| Birsay - eider nest. Not the most sensible place, given the number of passing humans! |

|

| Birsay dyke. Classic example of a basaltic intrusion – you could see it running for at least a mile (still in a very straight line) across the exposed foreshore. |

|

Across the water on the Hoy ferry

It is always good to step away from the car for a few days – taking the passenger ferry over to the unfashionable end of Hoy just added that little sense of adventure to the trip! Albert and Fay at Quoydale looked after us very well, and Albert even saw the rains coming in time to intercept us with the minibus on the return leg of our Old Man expedition. Hoy is Viking for ‘high island’ and it usually looks like this – the wind comes off the sea and the first cliff it hits rates about 1200ft (straight up) so there is always moisture in the air. The midges love it (apparently) but they were hardly in evidence at all on our trip – the dry spring must have helped.

The Dwarfie Stone

I think this takes the biscuit as the most weird artifact on the islands. One of the best descriptions is one of the first - see A Description of The Western Islands Of Scotland (c 1695) by Martin Martin for the original.

In the isle of Hoy there’s the Dwarfie-stone between two hills; it is about thirty-four feet long and above 16 feet broad; it is made hollow by human industry: it has a small square entry looking to the east, about two feet high, and has a stone proportionable at two feet distance before the entry. At one of the ends within this stone there is cut out a bed and pillow capable of two persons to lie in, at the other opposite end there is a void space cut out resembling a bed, and above both these there is a large hole which is supposed was a vent for smoke. The common tradition is that a giant and his wife made this their place of retreat.

The stone (or Stane depending on your Sco’ishness) has also led to some fairly bizarre theories in books of the “Uriel’s Machine” persuasion, of which the best seems to be its construction as a pressure-cell able to resist the flood caused by the legendary ‘Seven Stars in the Sky’ which gave Noah something to worry about. We will endeavour to add to the general air of mystification with a few random speculations of our own – the reader is warned!

| Dwarfie stone exterior. You can see the modern concrete fill which has stopped up the hole in the roof. Several similar boulders are lying nearby, having slid down from the cliffs above – no mystery here. The ‘blocking stone’ does seem to be a very good fit for the entrance, complete with accurate taper. |

|

| Dwarfie stone looking out. Recent literature usually describes this as a ‘rock-cut tomb’ which really doesn’t ring true at all. It is far to comfortable to be a tomb, for one thing, and there is clear wear on the entrance and the lip of the ‘bed’ inside. Whatever it was, it was regularly used over a long period. |

|

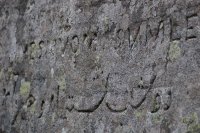

| Dwarfie stone - Persian graffiti. Also no mystery as the origin of these is well-known. Very pretty though! |

|

| Dwarfie stone - pyramid attachment point. Assuming this is a ‘stopper’ for the door, it would obviously need an attachment for a suitable anti-gravity device. You can just make out the triangle on the base where the pyramid was affixed. |

|

So what is it, and why is there nothing else like it anywhere? Maybe it’s just a tribute to the natural human tendency to hollow things out. It would make a great shepherd’s hut – the block is a superb storage heater and would be warm, dry and comfortable even in the worst winter weather. The ‘blocking stone’ could just be a stubby pillar which used to support the lower end to make the whole thing level – it has a boss very like the verticals at Stonehenge. Someone should jack it up and check for a matching mortice on the underside!

How did they do it? From the smoothness of the interior, I would say that it could only have been cut with some kind of anti-matter beam, so alien origin looks the best bet. Perhaps a visiting mission from Sirius-B took pity on some neolithic farmers and cut it out for them? Or of course it could be an early Christian attempt to reproduce Christ’s tomb in Jerusalem. Or maybe it is Christ's tomb, carefully cut out by the Templars and left here as the repository for the Holy Grail. Roslin was built by the Earl of Orkney, you know.

Time to move on …

Seeking out the Old Man of Hoy (the hard way)

Albert estimated a 7hr walk to make a circular tour from Quoydale via Berrie Dale to the Old Man and back up the coast via St Johns Head. He was not far out – we took the scramble down the back of the corrie at the Kame of Hoy which had lots of interesting aeroplane parts scattered down it (someone hit it rather harder than was good for them) and Albert kindly tracked us down in the van on the last leg home (just as the rains started properly).

| Berrie Dale. The most northerly native woodland in the UK, so a bit of a botanist’s paradise. Quite a hard scramble out of the top end. The red dot on the right is a rucksack with a human attached. |

|

| Old Man from the cliffs. Hard to get a proper sense of scale here, you’ll just have to go and see it for yourselves. |

|

| Richard taking a well-earned rest. Note the rather basic climbing gear … |

|

| Old Man with Campion in the foreground. Arty stuff again, I’m afraid! |

|

| Vertigo sufferers need not apply. Yes, there are humans in shot. Maybe they don’t appreciate how big an overhang lies below them, or maybe they just trust the rock to stay around for a few years more. |

|

| Geo on the way to St Johns Head. This edge really is dangerous – the stuff that looks like a Suffolk thatch is a very slippery rush (Great Woodrush – Luzula sylvatica) making the whole thing the human equivalent of the pitcher plant. Stay well back! |

|

| Vertical geology. Hard to get a feel for the drop, once the sea is so far below you can’t see the waves any more. |

|

| Looking down. The stack of Fulmars just went all the way to the bottom some 1000ft below. |

|

| St Johns Head. You can’t get right out to the sharp end, unfortunately – the part labelled Bre Brough on the map is cut off by a tricky 20ft crack. |

|

Heading home via Kinlochbervie and Inchnadamph

Just time for a quick look around Kirkwall, then back to the mainland for an overnight at Kinlochbervie (mainly to do the walk to Sandwood Bay) and the long drive south to St Andrews broken at Inchnadamph for a good look at the Durness Limestone where it very unexpectedly pops up right in the middle of the western highlands.

| St Magnus cathedral. Orkney was part of the Diocese of Trondheim for many years, and the cathedral seems to have been a statement of Viking pride. It is a very imposing example of late Norman architecture, all the more loveable for being built in the warm local sandstone. |

|

| Precambrian concrete at Sandwood Bay. Give this to any geology student (along with the burnt toast) for a guaranteed “You’re ’avin’ a larf” moment. |

|

| Sandwood dune system. The usual humans for scale. The brochures claim this as the best beach in the UK – the 4 mile walk certainly helps to keep it quiet. |

|

| Quinag with its head in the clouds. This was taken for the limestone pavement in the foreground – you could easily drive through here and never guess at the existence of a hidden corner of classic limestone scenery. |

|

| Fault plane with dry streambed. They don’t come much clearer than this! |

|

| Cave skimming. The boys reckoned they got a max of 8 bounces as the stones vanished into the cave. |

|

| Quinag showing its topknot. Probably means it’s going to rain. |

|

Wrap up

Guess what – it rained (and blew half a gale) all the way home – but we didn’t really care.